There’s something fascinatingly recursive about Hatton Garden—a place that transforms materials while being itself continuously transformed. This slender quarter-mile of London real estate offers a textbook case of what urban theorists call “adaptive reuse,” but with an alchemical twist: the very hands that reshape precious metals have simultaneously reshaped the district’s identity over centuries.

The story begins with a courtier’s dance—literally. When Sir Christopher Hatton’s galliard caught Elizabeth I’s discerning eye in the 1570s, he initiated a sequence of events that would transform a bishop’s orchard into what would eventually become the beating heart of Britain’s jewelry trade. The Queen’s pressure on the reluctant Bishop of Ely to lease his land to her favorite dancer represents a remarkable instance of how personal relationships at court could literally reshape urban geography.

What makes Hatton Garden particularly compelling is how it embodies the economic principle of path dependency—the way seemingly minor historical accidents create self-reinforcing patterns. The gradual migration of metal craftsmen from nearby Clerkenwell wasn’t orchestrated by any central planner but emerged organically through what economists call “knowledge spillover”—the invisible exchange of expertise that happens when specialists gather. This clustering effect intensified dramatically when South African diamond discoveries in the 1870s created new flows of capital and materials that found their gravitational center in this former aristocratic garden.

Each diamond cut in Hatton Garden today carries this strange historical lineage—from Elizabethan court politics to colonial resource extraction to specialized craft knowledge—a multifaceted history as complex as the stones themselves.

The Queen’s Dancer: How Sir Christopher Hatton Rose to Power

In the Elizabethan court—a treacherous ecosystem where strategic marriages, military heroism, and aristocratic lineage typically determined one’s trajectory—Sir Christopher Hatton represents a fascinating anomaly. Born in 1540 to middling Northamptonshire gentry, Hatton possessed neither battlefield glory nor ancient bloodlines, yet ascended to the highest echelons of Tudor power through what might be called the performance of devotion. His story offers a remarkable case study in how certain historical periods create idiosyncratic paths to influence—pathways that defy conventional career ladders.

In the Elizabethan court—a treacherous ecosystem where strategic marriages, military heroism, and aristocratic lineage typically determined one’s trajectory—Sir Christopher Hatton represents a fascinating anomaly. Born in 1540 to middling Northamptonshire gentry, Hatton possessed neither battlefield glory nor ancient bloodlines, yet ascended to the highest echelons of Tudor power through what might be called the performance of devotion. His story offers a remarkable case study in how certain historical periods create idiosyncratic paths to influence—pathways that defy conventional career ladders.

The pivotal moment in Hatton’s rise came at a court masque where his execution of the galliard—a vigorous five-step dance requiring considerable athletic prowess—caught Elizabeth’s discerning eye. This seemingly trivial social accomplishment would catalyze a decades-long relationship that culminated in his 1587 appointment as Lord Chancellor, despite having no formal legal training. Imagine a modern monarch appointing their favorite ballroom dancer as Chief Justice, and you begin to grasp the extraordinary nature of Hatton’s elevation.

The correspondence between Hatton and Elizabeth reveals the complex emotional choreography that paralleled his physical dancing. His letters, signed “Your faithful sheep” to her “Lyddes,” demonstrate what anthropologists might call “strategic vulnerability”—the careful deployment of devotion as a form of social capital. Their relationship epitomizes what historians Natalie Zemon Davis and Arlette Farge have called “emotional politics,” where affective bonds become instruments of governance in pre-bureaucratic states.

Hatton’s perpetual financial troubles—the constant scrambling for monopolies and land grants to support his court presence—illustrate what sociologist Thorstein Veblen would later call “conspicuous consumption.” The Elizabethan courtier found himself caught in what modern economists term a “positional arms race,” where maintaining status required increasingly unsustainable expenditure. Like many who rise through patronage rather than inherited privilege, Hatton discovered that access to power often demanded a ruinous performance of prosperity.

His involvement in the execution of Mary, Queen of Scots reveals how thoroughly Hatton had internalized the existential anxieties of the Tudor state. Having risen through personal loyalty rather than institutional position, he became one of the strongest advocates for eliminating threats to the monarch who had elevated him—his own security being inextricably bound to hers. When he died in 1591, deeply indebted but still in royal favor, Hatton left behind not a political dynasty but something ultimately more enduring: a patch of London real estate that would transform from a courtier’s garden into a global center of luxury trade, an evolution as improbable as his own remarkable career.

The Royal Land Transfer: How Church Property Became a Courtier’s Estate

When Bishop Richard Cox reluctantly signed away his London estate to Sir Christopher Hatton in 1576, he was participating in what historians might call “choreographed coercion”—a delicate performance where all parties understood the script but maintained the fiction of voluntary exchange. This transaction represents a fascinating case study in how property transfers in early modern England often functioned as material expressions of political relationships rather than straightforward economic exchanges.

The Ely Place estate—with its orchards, gardens, and imposing residence—had been ecclesiastical property since the 13th century, a remnant of the medieval church’s vast landholdings. By forcing its transfer to Hatton, Elizabeth was engaging in a subtle form of secularization, redirecting church resources to serve court politics without triggering the kind of dramatic confrontation that had characterized her father Henry VIII’s more aggressive seizures of church property. The queen had mastered what political scientists call “soft power”—achieving objectives through attraction and co-option rather than overt coercion.

The symbolic terms of the lease—£10 annually, ten loads of hay, and a single red rose presented to the Crown—reveal how this transaction existed in a liminal space between gift and market exchange. Anthropologist Marcel Mauss would have recognized this arrangement as a “total social phenomenon,” where economic, legal, moral, and aesthetic dimensions converge. The red rose, in particular, functions as what literary theorists call a “signifying object,” materializing the invisible bonds of obligation and patronage that structured Elizabethan politics.

Hatton’s subsequent renovation of the property illustrates what sociologist Pierre Bourdieu termed “conversion strategies”—the transformation of political capital (the queen’s favor) into cultural capital (architectural grandeur) and social capital (the ability to host influential gatherings). Hatton House became a three-dimensional assertion of its owner’s newly acquired status, a architectural proclamation of belonging among the elite. Yet this physical manifestation of royal favor came with a ruinous price tag that eventually contributed to Hatton’s financial collapse.

The irony of Hatton Garden’s evolution lies in how completely the space was transformed after its namesake’s death. While Hatton acquired the property as a status symbol in an economy of royal favor, it eventually became valuable for entirely different reasons in an emerging commercial economy. This transformation from courtly showpiece to commercial district exemplifies what economic historians call “adaptive reuse”—the repurposing of structures and spaces to serve new economic functions as societies evolve. The bishop’s garden, which became a courtier’s estate, would eventually transform into a merchant’s marketplace—each incarnation reflecting the shifting centers of power in English society from church to court to commerce.

Urban Transformation: Hatton Garden’s Evolution from Residence to Workshop

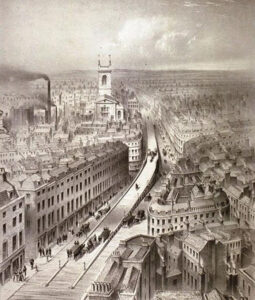

The fate of Hatton Garden following Sir Christopher Hatton’s debt-ridden death in 1591 offers a textbook example of what urban geographers call “succession”—the process by which neighborhoods transform their function and character over time. What makes this particular succession fascinating is how completely the area inverted its purpose while physically maintaining much of its original street layout, creating a palimpsest where commercial energy overwrote aristocratic leisure.

The fate of Hatton Garden following Sir Christopher Hatton’s debt-ridden death in 1591 offers a textbook example of what urban geographers call “succession”—the process by which neighborhoods transform their function and character over time. What makes this particular succession fascinating is how completely the area inverted its purpose while physically maintaining much of its original street layout, creating a palimpsest where commercial energy overwrote aristocratic leisure.

The dismantling of Hatton’s estate—the subdivision of his once-grand home into smaller units and the gradual leasing of garden parcels—mirrors what happened across London as the rigid hierarchies of Tudor society gradually gave way to the more fluid commercial relations of the 17th and 18th centuries. This wasn’t merely a change in occupancy but represented a profound shift in how urban space was conceptualized and valued—from a symbol of static social position to a dynamic site of economic exchange.

What drew the first wave of merchants and legal professionals to the area wasn’t just its prime location near Fleet Street and the Inns of Court, but what sociologists call “rent gap theory” in action—the economic opportunity created when a property’s actual use value falls below its potential market value. As Hatton’s heirs struggled to maintain the estate’s aristocratic character, savvy professionals recognized they could acquire prestigious addresses at declining prices, creating a feedback loop that accelerated the area’s transformation.

By the early 19th century, the district had undergone what Jane Jacobs would later call “unslumming”—evolving not through top-down planning but through the accumulated decisions of individual actors responding to market opportunities. The emergence of metalwork workshops and small manufacturing represents a classic case of what economic geographers term “industrial agglomeration”—the tendency of related businesses to cluster together to share knowledge, suppliers, and customers.

This clustering effect created what anthropologists call “communities of practice,” where tacit knowledge passes between practitioners through informal interactions rather than formal training. The silversmiths, watchmakers, and engravers who established themselves in Hatton Garden weren’t just renting space—they were buying into an ecosystem of expertise. Their specialized trades required precise skills that benefited from proximity to fellow craftspeople who could share techniques, refer customers, and collaborate on complex projects.

The transformation from Hatton’s aristocratic estate to a commercial district wasn’t just a change in land use but represented a fundamental shift in English society—from an economy of royal favor to one increasingly driven by commercial exchange and specialized craft knowledge. In this evolution, we can see the physical manifestation of Britain’s gradual transition from feudal structures to early capitalism, written not in political treatises but in the changing purpose of buildings along a quarter-mile of London streets.

The Diamond Connection: How South African Discoveries Transformed London Trade

The metamorphosis of Hatton Garden from metalworking district to global diamond hub offers a compelling case study in what economic geographers call “industrial upgrading”—the process whereby a specialized district evolves toward increasingly high-value activities. What makes this evolution particularly fascinating is how it resulted not from central planning but from the intersection of global commodity flows, specialized craft knowledge, and the transnational networks created by diaspora communities.

The metamorphosis of Hatton Garden from metalworking district to global diamond hub offers a compelling case study in what economic geographers call “industrial upgrading”—the process whereby a specialized district evolves toward increasingly high-value activities. What makes this evolution particularly fascinating is how it resulted not from central planning but from the intersection of global commodity flows, specialized craft knowledge, and the transnational networks created by diaspora communities.

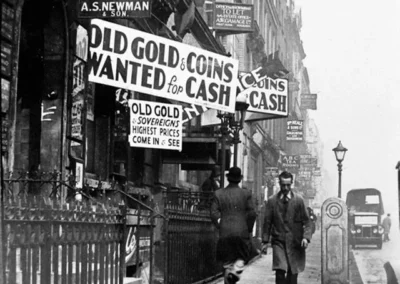

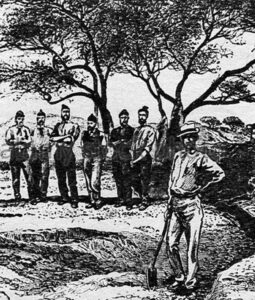

When the Kimberley and later Cullinan diamond fields were discovered in South Africa in the 1870s, they triggered what commodity historians call a “resource shock”—a sudden increase in supply that reconfigures global trade networks. London, as the metropolitan center of the British Empire, became the natural funnel for these newly extracted treasures. But why Hatton Garden specifically? The answer lies in what economic sociologists term “related variety”—the principle that new specialized activities tend to emerge in places where adjacent skills already exist. The district’s silversmithing and watchmaking traditions provided precisely the ecosystem of fine manual dexterity, materials knowledge, and precision tools that diamond work required.

Just as significant as the material flow of diamonds was the human migration that accompanied it. The Jewish diaspora communities that settled in Hatton Garden—many fleeing pogroms in Eastern Europe or seeking opportunity beyond Amsterdam’s established but saturated diamond trade—exemplify what sociologist Alejandro Portes calls “ethnic enclave economies.” These tight-knit communities brought with them not just technical expertise but, crucially, transnational trust networks that facilitated trade in objects of extraordinary value. In a business where millions could change hands on a handshake, these community-based trust mechanisms created competitive advantages that corporate structures struggled to replicate.

The rise of De Beers and its consolidation of global diamond production added another layer to Hatton Garden’s evolution. The company’s near-monopoly from the 1890s through much of the 20th century created what economists call a “vertical disintegration” of the supply chain—centralizing control of rough diamonds while allowing specialized cutting, polishing, and retail to flourish in distinct geographic clusters. Hatton Garden became one such node in this global network, specializing in the higher-value segments of the chain.

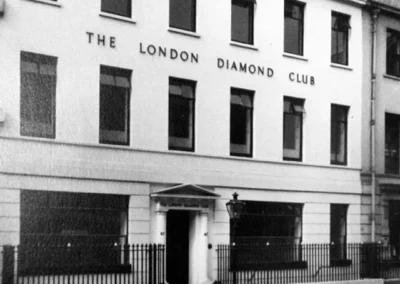

Today’s Hatton Garden represents what urban theorist Jane Jacobs called “new work in old places”—the continued evolution of specialized knowledge within a physically stable urban framework. Despite the digital revolution that has transformed most industries, the diamond trade remains stubbornly material, relying on face-to-face transactions and tacit knowledge that resists virtualization. The district’s hundreds of specialists—cutters, setters, dealers, and retailers—form what organizational theorists call a “community of practice,” where expertise is maintained and transmitted through apprenticeship and daily interaction rather than formal instruction.

What began as an aristocrat’s garden has become, through centuries of unplanned evolution, a place where global resource flows, specialized craft knowledge, migration patterns, and trust networks converge—a microcosm of how global capitalism actually operates not through abstract market forces alone but through socially embedded relationships that still, surprisingly, require physical proximity in our supposedly frictionless digital age.

Surviving Crisis: Hatton Garden Through War, Technology, and Famous Heists

The 20th century presented Hatton Garden with what systems theorists call “stress tests”—existential challenges that reveal an institution’s capacity for adaptation. The district’s response to these challenges—from wartime destruction to digital disruption—offers a fascinating case study in what organizational ecologists term “structural inertia versus adaptive capacity,” the tension between maintaining identity while evolving function.

The 20th century presented Hatton Garden with what systems theorists call “stress tests”—existential challenges that reveal an institution’s capacity for adaptation. The district’s response to these challenges—from wartime destruction to digital disruption—offers a fascinating case study in what organizational ecologists term “structural inertia versus adaptive capacity,” the tension between maintaining identity while evolving function.

The Luftwaffe bombs that rained down during the Blitz created what urban planners call “creative destruction”—devastating physical damage that paradoxically opened space for renewal. When jewelry workshops emerged from the rubble in the post-war years, they exemplified what economists call “path-dependent innovation”—rebuilding with new techniques while maintaining the district’s fundamental identity. These weren’t merely businesses being reconstructed but a knowledge ecosystem being preserved through what sociologists term “community memory”—the collective expertise that transcends individual craftspeople.

The post-war period coincided with what cultural historians identify as the “democratization of luxury”—the growing middle-class access to previously elite goods. Diamond engagement rings, once reserved for aristocracy, became cultural expectations propelled by Hollywood imagery and rising consumer affluence. Hatton Garden’s workshops, with their ability to create bespoke versions of these newly essential status symbols, positioned themselves perfectly at the intersection of mass aspiration and artisanal authenticity.

The post-war period coincided with what cultural historians identify as the “democratization of luxury”—the growing middle-class access to previously elite goods. Diamond engagement rings, once reserved for aristocracy, became cultural expectations propelled by Hollywood imagery and rising consumer affluence. Hatton Garden’s workshops, with their ability to create bespoke versions of these newly essential status symbols, positioned themselves perfectly at the intersection of mass aspiration and artisanal authenticity.

By the digital turn of the 21st century, Hatton Garden faced what Clayton Christensen famously termed “the innovator’s dilemma”—how to embrace technological change without abandoning core competencies. The district’s most successful businesses enacted what management theorists call “ambidextrous innovation”—simultaneously preserving traditional craft knowledge while adopting CAD design, laser cutting, and e-commerce platforms. Rather than seeing technology as a threat to craftsmanship, they recognized it as a tool that could amplify their traditional strengths.

Perhaps nothing better illustrates Hatton Garden’s enduring cultural significance than the 2015 heist—a crime that captured public imagination precisely because it targeted a place that still represents authentic value in an increasingly virtual economy. The elderly criminals, with their drills and determination, unwittingly paid tribute to the district’s continued relevance—you don’t rob places that don’t matter. That this physical theft became instant fodder for digital entertainment (documentaries, films, podcasts) perfectly embodies Hatton Garden’s ability to exist simultaneously in material and media spaces—a place where tangible craft and intangible stories continuously intersect, ensuring its cultural significance extends well beyond the quarter-mile of London streets it physically occupies.